When the music’s over…

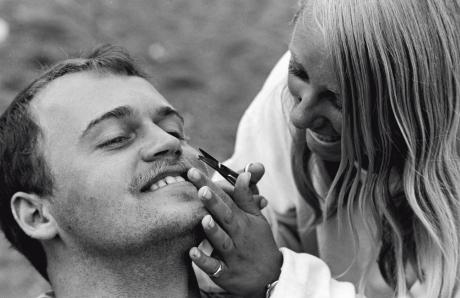

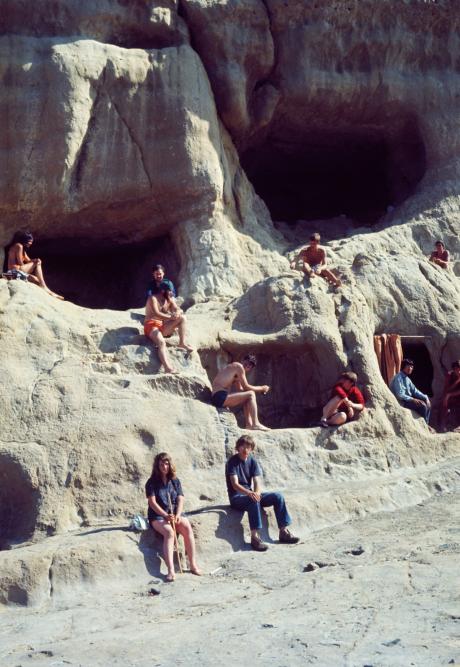

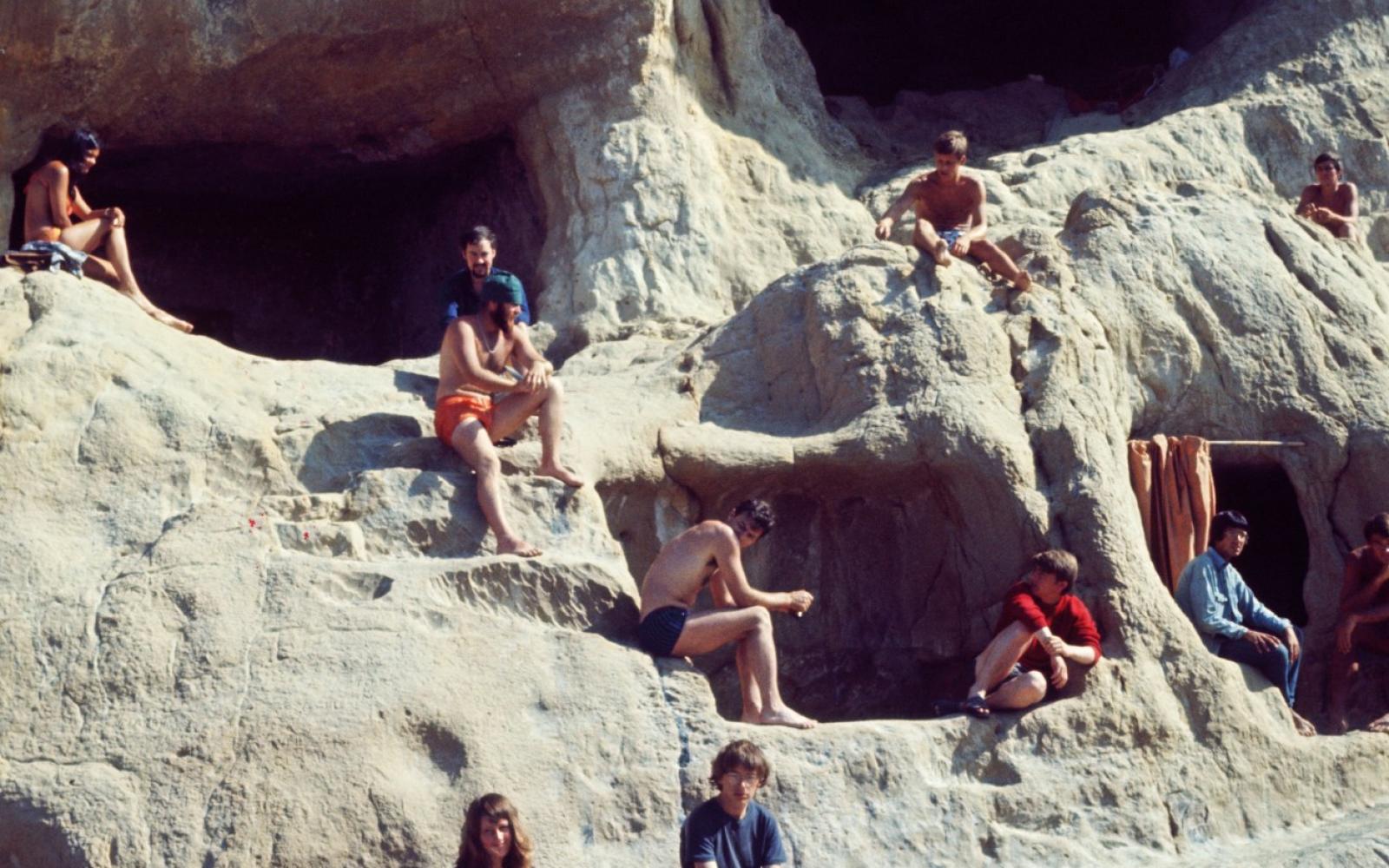

In defiance of a petty bourgeois establishment, the beatnik movement in 1950’s America began sowing seeds of dissent within their own marginalised subculture. A decade later in Crete, individuals associated with that subculture – beatniks, hippies and other castaways, began populating the caves of Matala. These were restless spirits, all of them revolutionaries in search of a life of substance-educated young people, including many Harvard graduates, appalled at the misery bred by consumerism. The flower children made the caves their home, lit them with oil lamps, wore colourful clothes or none at all, sang rock and roll songs, worked in the fields for little money, bathed and swam and fished for their food – basking in the freedoms of the Mediterranean Sea.

The villagers weren’t bothered. But, high-ranking officials and part of the press persistently demanded the removal of the “vulgar” and “unbalanced” squatters from the region. News travelled abroad fast. In 1968, Life magazine published a photograph on its cover of a young couple in Matala. The excellent reportage by Thomas Thompson and the stunning photographs by Denis Cameron introduced a prehistoric, earthly paradise to those in search of one. Within a day, the hitherto unknown fishing village and caves of Matala became a worldwide sensation attracting hippies in droves.

As the movement grew, so did the voice of dissension among leaders who fought it. Police conducted surprise raids on the hippie enclave, the Orthodox church preached about the “evil tree of degenerates” that needed uprooting before the children of Crete entered its shadow, and the media lapped it up– pushing provocative articles into the newspapers. There was a war of attrition until, in the early 70s, Stelios Xagorarakis, a native of Crete and owner of the famous Mermaid Café, came forward and spoke of the hippies in a positive light to the local press, claiming the war against them would destroy the island’s tourism. “Cease fire” became headline news. The climate changed and calm prevailed – as it always does before unleashing the storm.

At the time, Greece was under the dictatorship of George Papadopoulos, who did not take a stance initially on the Matala issue. Though disgusted by the situation, he feared backing any sweeping operation – a move that could undermine his “democratic” principles in the public eye. Eventually, he would crack under pressure from the local clergy. In May of 1970, police swarmed the caves, arresting most of their occupants. Overnight, the scene changed completely. As governmental authority transitioned in 1977, the caves of Matala were emptied and closed off permanently. The music was silenced. The utopian dream was over.

Image gallery

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Ancient Symposium

Timeless Charm

Guardians of Tradition